- Self-Study Guided Program o Notes o Tests o Videos o Action Plan

© 2019 The Indian Express Ltd.

All Rights Reserved

The writer is chair professor for agriculture at ICRIER. Views are personal

Last week, as the Air Quality Index (AQI) touched emergency levels in the National Capital Region, the Supreme Court came down heavily on the chief secretaries of four states — Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Delhi. They were berated for their failure to “give clean air to Delhi residents”. Paddy stubble burning in states neighbouring Delhi, especially Punjab, is being seen as one of the reasons for the smog in the national capital. The honourable judges of the apex court have asked the Punjab government to pay Rs 100 per quintal to farmers as an incentive for desisting from burning stubble. Solutions such as subsidising Happy Seeders are also being talked about. But these solutions seem to be scratching the surface of the paddy problem.

The problem is much deeper than stubble burning and nothing will be served by pulling up chief secretaries of Delhi’s neighbouring states. The solution to the problem rests with the political class — both in the Centre as well as in these states. It is the elected representatives, and not bureaucracy, who make policies for grain management.

The Punjab-Haryana region was not India’s rice belt, before the Green Revolution. Punjab was known for “makki ki roti and sarson ka saag”, but now it is rare to see makki (corn) in the state. Much of the kharif area in the region is under rice — about 3.1 million hectares in Punjab and 1.4 million hectares in Haryana. This has caused havoc with the groundwater table that has been depleting at about 33 cms each year. Groundwater in more than three-fourths of blocks in Punjab is over-exploited. Paddy cultivation in this belt is against the region’s natural water endowment.

In order to save water during the peak summer season, the Punjab government passed a law in 2009 outlawing paddy sowing before June 15. This pushes the rice harvesting to the late October-mid-November period, leaving very little time for sowing the rabi crop, mainly wheat. Farmers rely on paddy harvesters that leave stubbles, which are then burnt to make the field ready for sowing wheat. Farm labour has become expensive, especially during the peak season.

The question one needs to ask is why have Punjab and Haryana gone in a big way for paddy cultivation when their water resource endowment does not align with the crop’s requirement. One kilogram of rice requires about 5,000 litres of irrigation water in this belt. And, the natural rainfall is too less for the purpose. Farmers cultivate paddy as it gives them higher profits, compared to competing crops like corn. The key reasons for that are the massive subsidies on power provided by the state government and fertiliser subsidy given to them by the Centre. Moreover, they are assured procurement of paddy by state government agencies on behalf of the Food Corporation of India.

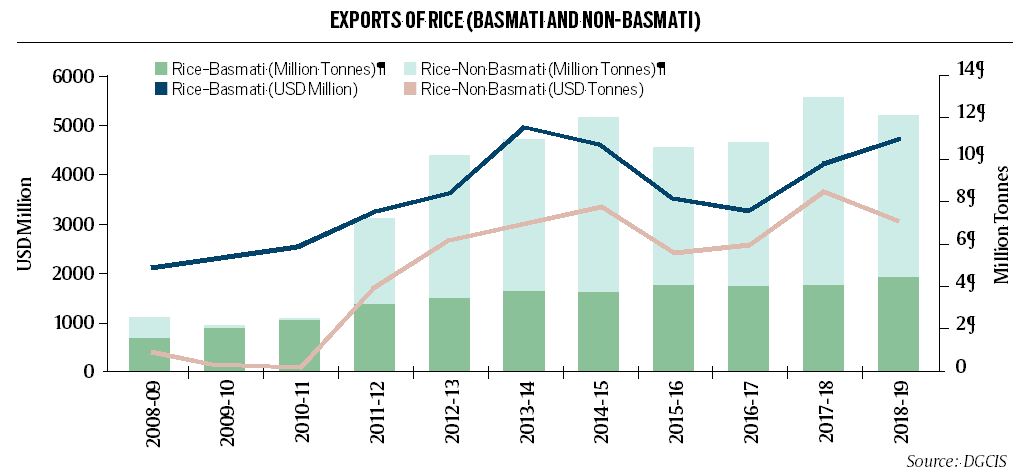

In the eastern parts of the country, water is available much more abundantly. About two million hectares of rice growing area in the northern belt needs to shift to this part of the country. The basmati-growing area in the Northern belt is about 1.2 million hectares; it produces 4.6 million tonnes of basmati. But the value of basmati is almost three times higher than that of common rice and much of that is exported (see figure-1). So Punjab and Haryana should focus on cultivating basmati, that is known to give three times higher value for every drop of water. The states should try to get away from common paddy, which is largely meant for the Public Distribution System — PDS rice is being sold at Rs 3/kg under the National Food Security Act.

How can one encourage farmers to shift from paddy to, say, corn? That boils down to policy, both at the Centre and state-level. Can the Centre and the states abolish the fertiliser and power subsidies? The chances of that happening are remote, given the place of free power and cheap fertilisers in the country’s political discourse. A move towards giving these subsidies in cash on per hectare basis to farmers can lead to some improvement. Farmers could be encouraged to change their crop preference if the Centre and the Punjab and Haryana governments announce a cash incentive of Rs 12,000 per hectare — shared equally between the Centre and the states — for growing corn in place of paddy. Our calculations suggest that the combined subsidy on power for irrigation and fertiliser in paddy cultivation is about Rs 15,000/ha. So, giving Rs 12,000/ha for corn cultivation actually is transferring the subsidy from rice cultivation to corn cultivation. It will not cost the state or central exchequer anything extra. Moreover, corn cultivation will have to be absorbed, not by government procurement but by feed mills for poultry, starch mills and ethanol. So, tax incentives for the corn-based industry in this belt could create a more market-aligned demand for corn.

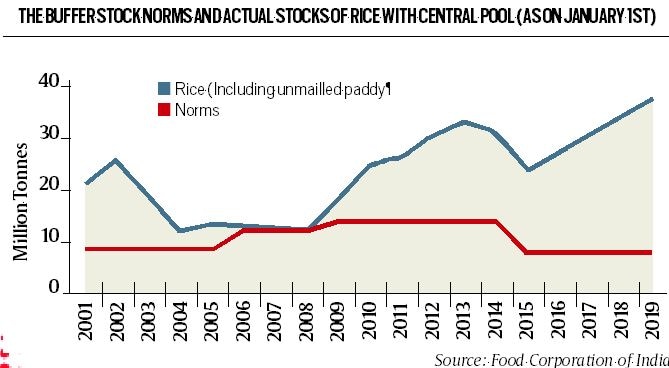

This is just the right time to make this switch from paddy to corn as rice stocks with government are way above the buffer stock norms (see figure-2). This speaks of massive inefficiency in grain management. In fact, the Centre should announce that it will not procure more than say 50 per cent of production of common paddy from the blocks that are over-exploited. Further, it will not give to the state procurement agencies more than 4 per cent as commission, mandi fee, or any cess for procuring on behalf of FCI.

An incentive of Rs 12,000/ha to the farmer to switch from paddy to corn and cutting down procurement from overexploited blocks may accomplish what the Supreme Court’s hauling up of the chief secretaries may not.

The writer is Infosys Chair Professor for Agriculture at ICRIER

Download the Indian Express apps for iPhone, iPad or Android

© 2019 The Indian Express Ltd. All Rights Reserved