- Self-Study Guided Program o Notes o Tests o Videos o Action Plan

© 2019 The Indian Express Ltd.

All Rights Reserved

The writer is chair professor for agriculture at ICRIER. Views are personal

Ritika Juneja is Research Assistant at ICRIER.

Normally, a sector’s credit off-take is a sign of its health. Higher the off-take, the better the sector’s performance. There has been a healthy off-take of ground-level credit (GLC) in agriculture and allied sectors. In the financial year (FY) 2018-19, banks disbursed Rs 12.55 trillion as GLC to agriculture, surpassing the government’s target of Rs 11 trillion. This should be cause for celebration but, unfortunately, the agriculture sector’s performance has not been commensurate with the credit that it has received. What has gone wrong? Let us go into some lesser-known facts about agri-credit in India to answer this question.

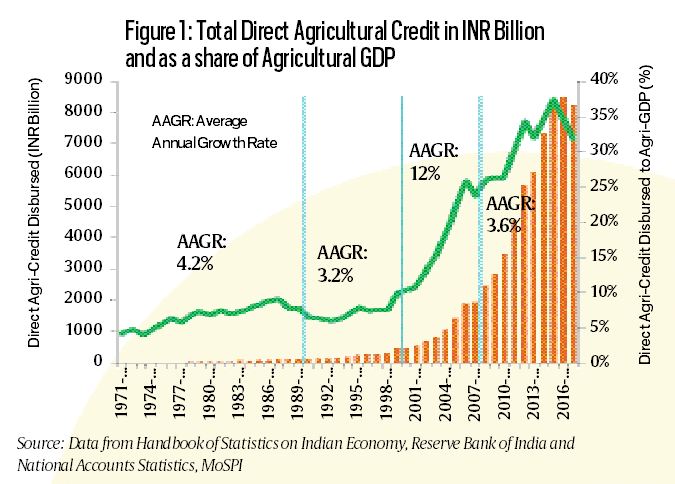

Figure 1 presents the absolute amount of direct institutional credit flow to the agriculture sector. There is no doubt that over a more than 40-year period, from 1971-72 to 2017-18, there has been a more than 1,000 time increase in agri-credit — from a meagre Rs 7.8 billion to Rs 8,235 billion. However, as a percentage of the agricultural GDP, which should be the real measure of agri-credit growth, the rise has not been smooth. For example, during the pre-reform period (1971-72 to 1989-90), direct agri-credit flow as percentage of agri-GDP increased at a modest average annual growth rate (AAGR) of 4.2 per cent. However, during 1990-91 to 1999-2000, AAGR decelerated to 3.2 per cent per annum. But during 2000-01-2007-08, it witnessed a tremendous growth at 12 per cent per annum, only to fall back to just 3.6 per cent per annum in the period between 2008-09 and 2017-18. The massive growth during 2000-01 to 2007-08 appears to be due to an innovative credit instrument, the Kisan Credit Card (KCC), and a policy intervention, the Interest Subvention Scheme, which incentivised short-term credit. The slowdown after 2008 appears to be due to a loan waiver scheme, which led bankers to be more conservative in lending to farmers. Bankers feared that farmers will default on their loans because they expect loan waiver schemes.

Interestingly, the All India Financial Inclusion Survey (NAFIS) of 2015-16 by NABARD reported that 30.3 per cent of all agriculture households availed credit from institutional sources. It could be said that the remaining agri-households either don’t need credit or they are not “bankable”, or both. However, the fact that almost 70 per cent of agri-households did not avail institutional credit shows that there is much scope for the banking sector to extend its reach — be it lending for production purposes (crop loans), investment or even consumption purposes.

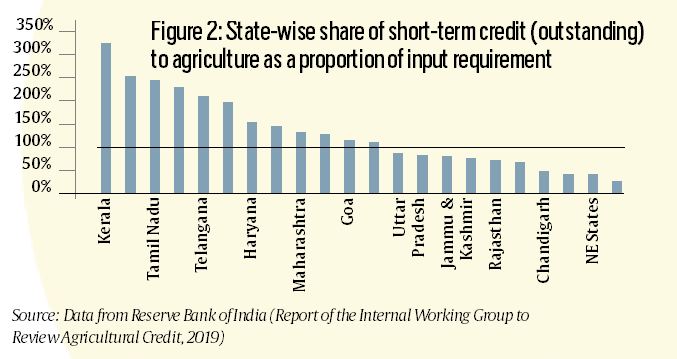

The Centre started an interest subvention scheme in 2006. This involved giving crop loans to farmers at 7 per cent interest rate; those who paid their loans back regularly would then get crop loans at a 4 per cent interest rate. This is usually done in a situation when the informal sector’s interest rates — even the rates of micro-finance institutions — range from 15-30 per cent. The scheme created opportunities for farmers to take crop loans at subsidised interest rates from the banking sector and then divert them for non-agriculture purposes. An idea of this diversion of agri-credit to non-agricultural purposes can be had by looking at agri-credit as a percentage of the value of input requirements in agriculture.

Figure 2 presents the state level picture for the triennium average ending (TE) 2016-17. The total short-term credit (outstanding) to agriculture and allied sectors as a proportion of input requirements (GVO-GVA) was substantially above 100 per cent for many states in South and North India — Kerala (326 per cent), Andhra Pradesh (254 per cent), Tamil Nadu (245 per cent), Punjab (231 per cent), Telangana (210 per cent). This is a clear indication that agri-loans are being diverted for non-farm purposes. One reason for this diversion is the low interest rate being charged under the interest subvention scheme.

Another interesting feature is that in the total direct credit (outstanding) to agriculture and allied sectors, the share of short-term credit witnessed a significant jump from 44 per cent in 1981-82 to 74.3 per cent in 2015-16 whereas, somewhat worryingly, the share of long-term credit fell from 56.1 per cent in 1981-82 to 25.3 per cent in 2015-16. Since long-term credit is basically for investments and capital formation in agriculture, this dramatic fall in the share of such credit takes a heavy toll on farm productivity and the overall growth of the agri-sector.

It is, therefore, high time to revisit the interest subvention policy, which is leading to sub-optimal results in the agriculture sector. For the sake of transparency, all crops loans, especially those availing interest subvention, should be routed through Kisan Credit Cards. The last Economic Survey reported that 150 million such cards had been issued by March 2016. But the NAFIS survey reported that only 10 per cent of farmers used such cards in the agricultural year 2015-16. The reluctance of farmers to use Kisan Credit Cards requires more research. Even then, the issuing of these cards in remote villages needs to be expedited.

A bolder step in this direction would be to empower farmers by giving them direct income support on a per hectare basis — rather than hugely subsidising credit. Streamlining the agri-credit system to facilitate higher crop loans to farmer-producer organisations against commodity stocks can be a win-win model to spur agriculture growth. Can the government plug the diversion and make the agri-credit system more efficient and inclusive?

Gulati is Infosys Chair Professor for Agriculture and Juneja is Consultant at ICRIER

Download the Indian Express apps for iPhone, iPad or Android

© 2019 The Indian Express Ltd. All Rights Reserved