- Self-Study Guided Program o Notes o Tests o Videos o Action Plan

© 2019 The Indian Express Ltd.

All Rights Reserved

The writer is chair professor for agriculture at ICRIER. Views are personal

A one-week delay in the monsoon’s arrival has laid bare the precariousness of India’s water situation. The images of thousands of Chennai residents running after water tankers were telecast by BBC and CNN. Several people had to walk for miles to get drinking water in parched lands. If this was the condition of humans, one can imagine the condition of cattle. These images clearly exposed that the Indian lion, the symbol of Make in India, has feet of clay.

It is no wonder that Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in the first ‘Mann ki Baat’ of his second term, gave a clarion call to save every drop of water, and to make water conservation a mass movement on the lines of the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan. He already has given a commitment to deliver tap water, hopefully safe for drinking, to every household by 2024 under the “Nal se Jal” programme. These are commendable measures and one hopes they can deliver quality results in time.

But the issue that we want to dwell on here is: How did we reach the current situation? And how best, and how fast, can we get out of it for sustainable water-use in the country?

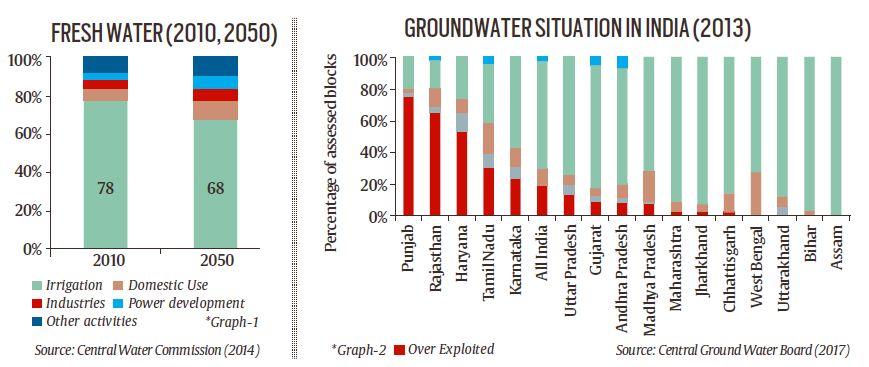

First, let us note a few facts about water availability and use in India. India has only 4 per cent of the global fresh water resources while it has to quench the thirst of about 18 per cent of the world population. Of the total fresh water resources available in the country, as per the Central Water Commission, 78 per cent was being used for irrigation in 2010, which is likely to be reduced to 68 per cent by 2050. For domestic use, it was just 6 per cent in 2010, likely to go up to 9.5 per cent by 2050 (graph 1). So, by far, agriculture will remain the biggest user of water to produce enough food, feed and fibre for the foreseeable future. And unless this sector is geared to improve in terms of the supplies of and efficiency in water use, the situation is not going to improve significantly.

Second, of the total of about 198 million hectares of India’s gross cropped area, roughly half is irrigated. And the major source of this irrigation is groundwater (63 per cent), canals accounting for 24 per cent, tanks 2 per cent and all other sources accounting for about 11 per cent. So, the real burden of irrigating Indian agriculture lies with groundwater, driven by private investments from farmers.

There is hardly any effective regulation of groundwater. The policy of cheap or free power supply for irrigation has led to a situation of near-anarchy in the use of groundwater. On the one hand, power subsidies to agriculture cost the exchequer roughly Rs 70,000 crore each year and on the other, this is depleting groundwater in an alarming manner. Overall, about 1,592 blocks in 256 districts are either critical or overexploited. In places like Punjab, the water table is going down by almost a metre a year, and this has been going on for nearly two decades. Almost 80 per cent of the blocks in Punjab are over-exploited or critical (see graph 2). This only shows how indifferent and short-sighted we are while taking away the rights of our own future generations.

Paddy and sugarcane, both water-guzzling crops, take away almost 60 per cent of India’s irrigation water. One kilogram of rice produced in Punjab requires almost 5,000 litres of water, and one kg of sugar, say in Maharashtra, requires about 2,300 litres of water for irrigation. Estimates vary on how much water the plant really consumes, how much evaporates, and how much of it goes back into groundwater. But traditionally, say a hundred years ago, eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar used to be the hubs for sugarcane, and rice was grown largely in eastern and southern India, where rainfall was high and water plentiful. All that changed with new technology and populist policies like free power.

No political party wants to touch the rationalisation of power pricing for agriculture. Technological solutions like drip irrigation, sprinklers, etc. cannot make much headway unless policies are put on the right track. Israel has perhaps the best water technologies and management systems, ranging from drips to desalinisation to recycling (87 per cent) of urban waste water for agriculture. PM Modi visited Israel to find solutions to our water woes. But my visits to Israel revealed one thing clearly: Technologies cannot take you far enough unless the pricing of power and irrigation water is put on track.

One possible way out is to give monetary rewards to farmers for saving water and power for irrigation. The existing situation can be taken as a sort of current entitlement, and those who agree to get their power supply metered and if they save on power consumption compared to current levels, can be rewarded. Along with that, there could be an income support (of say Rs 15,000/ha) for crops that guzzle less water, say maize or soyabean in Punjab during the kharif season. This would provide savings on the power subsidy, but more importantly, in terms of precious groundwater. At least one million hectares of paddy cultivation needs to shift away from the Punjab/Haryana belt to eastern India. Eastern India can develop better procurement facilities for paddy for the PDS, and procurement from Punjab-Haryana needs to be discouraged/curtailed.

Similarly, sugarcane needs to be contained in the Maharashtra-Karnataka belt and expanded in the UP-Bihar belt. With new Co 0238 varieties that give recovery rates of more than 10.5 per cent, there is a good case that cane can be developed for ethanol from this belt. Will Modi 2.0 move in this direction to save water? Only time will tell.

Gulati is Infosys Chair Professor for Agriculture at ICRIER

Download the Indian Express apps for iPhone, iPad or Android

© 2019 The Indian Express Ltd. All Rights Reserved