- Self-Study Guided Program o Notes o Tests o Videos o Action Plan

© 2019 The Indian Express Ltd.

All Rights Reserved

The writer is chair professor for agriculture at ICRIER. Views are personal

As per the last report of National Statistical Office (NSO) released on May 31, the Gross Value Added (GVA) at basic prices (2011-12 prices) for the fourth quarter (Q4) of 2018-19 has slumped to 5.7 per cent for the overall economy, 3.1 per cent for manufacturing, and -0.1 percent for agriculture, forestry and fishery. However, for the entire financial year, FY19, GVA growth is more respectable — 6.6 per cent for the economy, 6.9 per cent for manufacturing and 2.9 per cent for agriculture.

Incidentally, for the Narendra Modi government’s first five-year stint (2014-15 to 2018-19), agri-GDP grew at 2.9 per cent per annum. Many experts believe that agriculture cannot grow at more than 3 per cent per annum on a sustainable basis. Swaminathan A Aiyar, for example — whose brilliant writings I admire — has recently written that “no country has managed more than 3 per cent agricultural growth over a long period”.

This is not correct. China, for example, registered an agri-GDP growth of 4.5 per cent per annum during 1978-2016, a very long period indeed. In fact, the first thing Chinese government did in 1978, when it started off economic reforms was to reform agriculture. Agri-GDP in China grew at 7.1 per cent per annum during 1978-84, and because the Chinese government also liberated price controls on agri-commodities, farmers’ real incomes increased at 15 per cent per annum. That set the stage for the manufacturing revolution, which was revved up through town and village enterprises (TVEs) to cater to domestic demand from rural areas. The rest is history.

Indian industry is today complaining that the rural demand is collapsing. Tractor sales are down by 13 per cent, two-wheeler sales are down by 16 per cent, car sales are down by similar percentage, and even FMCG (fast move consumer goods) sales are down in April 2019 over April 2018. One of the reasons is that India has never had any major agri-reforms and farmers’ incomes have remained very low. But there have been periods, reasonably long enough, when agri-GDP has grown well above 3 per cent. In fact during the 10 years of UPA from 2004-05 to 2013-14, agri-GDP grew at 3.7 per cent per annum. This dropped to 2.9 per cent during the NDA’s stint between 2014-2019. When the masses do not gain, the demand for manufactured goods remains limited, slowing down the wheels of industry. So, if industry wants to prosper, we must aim at an agri-GDP growth of more than 4 per cent. My assessment is that it can grow even at 5 per cent per annum at least for a decade, provided we are focused on reforming this sector.

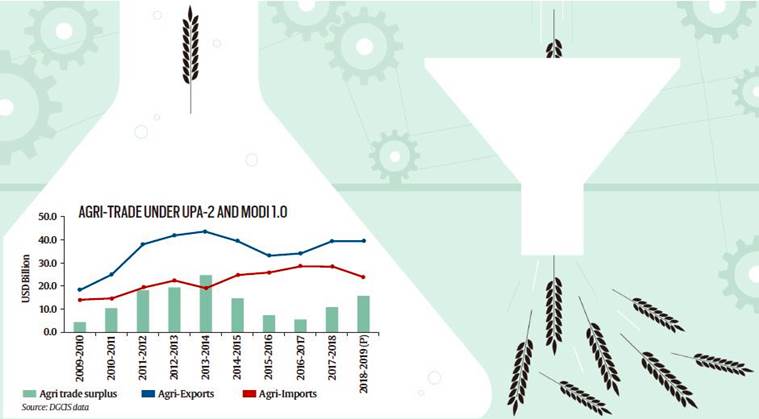

For that, we need to raise farm productivity in a manner that can cut down unit costs and make Indian agriculture more competitive, enabling higher exports. Unfortunately, agri-exports had a negative growth during Modi 1.0 (see graph).

During UPA-2, agri-exports more than doubled, from $18.4 billion in 2009-10 to $43.6 billion in 2013-14. But during Modi 1.0, they declined, going down to $ 33.3 billion in 2015-16 and then recovering to $ 39.4 billion by 2018-19 — but still below the peak of 2013-14.

Officials managing agri-trade need to pay heed to this massive failure as it has implications not only for overall agri-GDP growth, but also for slowing down of manufacturing growth due to sluggish demand for industrial products in rural areas. There is ample evidence that much of Indian agriculture is globally competitive. But our restrictive policies constrain the private sector from building direct supply chains from farms to ports, which bypass the mandi system. This leads to a weak infrastructure for agri-exports. The net result of all this is that Indian farmers do not get full advantage of global markets. Further, an obsessive focus on inflation targeting by suppressing food prices through myriad controls works against the farmer. If these policies continue, Prime Minister Modi’s target of doubling farmers’ real incomes by 2022-23 will remain a pipe-dream.

It has to be noted that any attempt to artificially prop up farmers’ prices through higher minimum support prices (MSPs), especially in relation to global prices, can be counterproductive. Normally, MSPs remain largely ineffective for most commodities in larger parts of India. But even if they are operational through massive procurement operations, a policy of high MSPs can backfire when it goes beyond global prices.

Take the case of rice. India is the largest exporter of rice in the world, exporting about 12 to 13 MMT of the cereal per year. If the government raises the MSP of rice, by say 20 per cent, rice exports will drop and stocks with the government will rise to levels far beyond the buffer stock norms. It would be a loss of scarce resources. Besides, it would create unnecessary distortions adversely impacting the diversification process in agriculture towards high-value crops. This needs to be avoided.

Our global competitiveness in agriculture can be bolstered by investment in agri-R&D and its extension from lab to land, investment in managing water efficiently and investment in infrastructure for agri-exports value chains. Today, India spends roughly 0.7 per cent of agri-GDP on agri-R&D and extension together. This needs to double in the next five years. The returns are enormous. The meagre investments in Pusa Basmati 1121 and 1509, for example, have yielded basmati exports between $ 4 and 5 billion annually. The returns from the sugarcane variety Co-0238 in Uttar Pradesh are similarly impressive. The recovery ratio has increased from about 9.2 in 2012-13 to more than 11 per cent today. Massive investments are also needed in managing our water resources more efficiently, to produce more with less.

But augmenting productivity alone — without pushing for export markets — can lead to glut at a home and depress farm prices, shrinking their profitability. So, first think of markets and then give a push to raise productivity and exports simultaneously.

Can all this be done under Modi 2.0? Only time will tell.

The writer is Infosys Chair Professor for Agriculture at ICRIER

Download the Indian Express apps for iPhone, iPad or Android

© 2019 The Indian Express Ltd. All Rights Reserved